Golden Ages of Civilization

People take progress for granted.

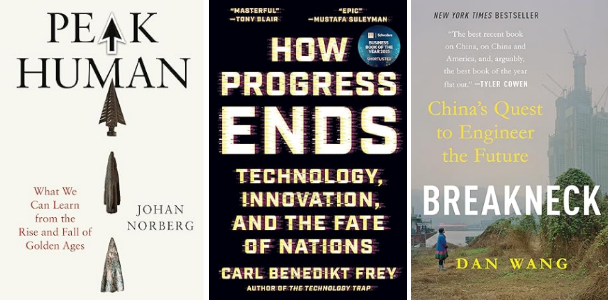

People take progress for granted. If you've known nothing but peace and prosperity, expecting it to continue feels natural. This review covers three books that explore this topic:

- Peak Human: What We Can Learn From History's Greatest Civilizations by Johan Norberg

- How Progress Ends: Technology, Innovation, and the Fate of Nations by Carl Benedikt Frey

- Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future by Dan Wang

I believe that people take progress for granted. And this makes sense: if you’ve known nothing but peace and prosperity in your lifetime, it’s the most natural thing to expect it to continue. I don’t believe this is the natural state of affairs or a stable equilibrium.

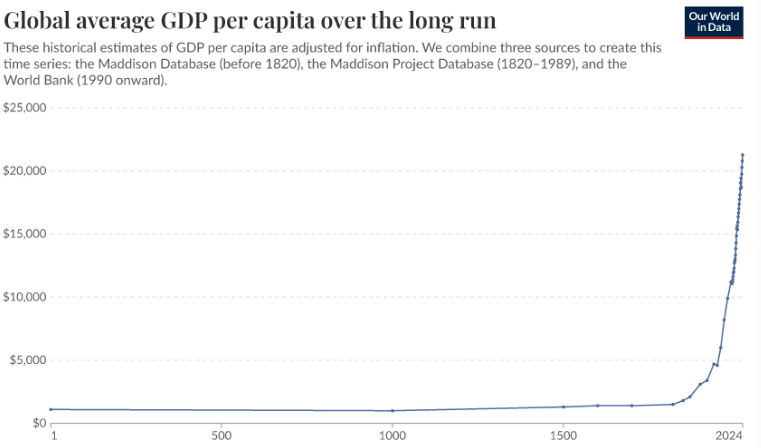

Both Peak Human and How Progress Ends study historical societies. This is one of my favorite plots highlighting how weird today is compared to most of history:

Another sobering fact is that a lot of golden ages ended due to an external shock, whether it was the Mongols ending the Song dynasty’s golden age or invasion ending the Dutch golden age or the late antique little ice age causing Roman food production to collapse from 250 AD onward. Plague has also been a significant factor in weakening empires.

Golden ages are unstable!

Peak Human

Peak Human profiles seven golden ages: Periclean Athens, the Roman Republic, the Abbasid Caliphate, Song China, Renaissance Italy, the Dutch Republic, and the Industrial Anglosphere. Norberg identifies a pattern: golden ages often begin with decisive military victories that breed confidence, benevolence, and openness to new people and ideas.

A trend that Norberg identifies is that each empire often begins with a great military victory, allowing that empire to be confident, benevolent, and open to people and ideas. For Greece it was the idea of Democracy and for Rome it was the expansion of what it meant to be a citizen and there are similar examples for the rest of the group. The next stage is prosperity and growth.

But at some point, society is met by an external threat which leads society to defensively impose orthodoxies. The wealth of Song China in the 1200s led to the attention of outside forces, especially the Mongols. This threat caused the state to turn inwards. The Dutch Republic’s golden age ended when France stabilized and became much stronger under Louis XIV and decided to invade. The previous confidence and openness of the Dutch regressed into a closed society. The response to crises laid the seeds of the collapse.

A simple mental model that comes out of this study is that golden ages are hard to sustain because they need to successfully adapt to a series of challenges. Failing any one of these adaptations (not being militarily strong enough, not being resilient to climate disaster) leads to societies closing down and losing the ability to adapt just when they most need to adapt. Once societies lose this dynamism, the decline often accelerates.

Norberg believes that “No classic civilization came as close to unleashing an industrial revolution and creating the modern world as Song China.” The idea leads to a fascinating thought experiment: what if China were luckier with its neighbor or that horses were not native to the steppe? Would the industrial revolution we know in textbooks begin in the 1300s? Similarly, Churchill credits the miraculous Mongol retreat in 1242 as having saved Europe and allowing for the conditions for the Renaissance 2 centuries later (by not unifying Europe at the time).

This leads us to the question of centralization which is covered in How Progress Ends.

How Progress Ends

Frey broadly categorizes effective governments as two types: centralized and decentralized. Centralized governments are often highly authoritarian, directive, and impose a large degree of control in their citizens' lives. Modern China is a good example of this. A decentralized government is the opposite and generally leaves citizens alone.

Frey’s thesis is that centralized governments are great at catch-up growth (‘exploitation’ of existing technology) but less good at driving future innovation (‘exploration’ of new technology).

Centralized governments can mandate “best practices” and favor specific industries. This works when there is some general playbook to copy and a way to catch up. Germany, The USSR, Japan, Korea, and China are all examples of states that did this highly effectively in the last 170 years. All of these states did eventually hit a wall when growth needed to be innovation-led (except for China, which is still growing and much poorer than Korea or Japan on a per-capita basis).

Korea may have been one of the standout successes in this regard with its very smart emphasis on export targets. While the centralized government was heavy-handed in mandating specific targets and providing support, the government also allowed an external source of feedback (export markets) to be the barometer of success for various companies. Japan has historically been thought of also doing this well, but Korea’s catch-up growth started a bit later and recently surpassed Japan’s GDP per capita on some measures.

The United States exemplifies the strengths of a decentralized society. Some examples:

- The federal system: due to the nature of how the US was founded, there is a relatively strong set of states rights allowing for a lot more policy experimentation that would ordinarily exist at a centralized level. When the states were unifying, they had very different economies and societies which led to strong states rights protections in the constitution.

- ARPA and the university system. Frey highlighted the post world war 2 research consensus as a particularly strong example of decentralization working well to drive scientific progress forward. In particular, by funding a lot of science at a lot of universities, there were no centralized veto points of research. This was incredibly valuable in attracting the best scientists as well as overturning scientific orthodoxy as needed to drive progress.

- Silicon Valley and California labour laws. Labor laws in California are extremely friendly to employees, outlawing restrictive covenants like non-competes. This means that knowledge diffuses quickly in the valley and makes the entire ecosystem much more effective at driving progress.

Examples of successful decentralization over time are rare. Decentralization suffers the risk capture leading to recentralization. As the economy becomes increasingly winner-take-all, the incentives and rewards to state capture become even more compelling. This is a red flag risk right now in the US as our guardrails against corruption have been rotting or are being actively dismantled.

A state effective at maintaining the right balance needs to actually be strong enough to encourage competition and continually resist capture or stagnation. The true strength of decentralization is that new ideas can continually be explored. This brings us to Breakneck which tries to profile contemporary US and contemporary China and diagnose which types of capture best describe each state.

Breakneck

Wang suggests that China is effectively an engineering state and the US is a lawyerly society. They both have strengths and weaknesses.

Engineering states can build things. Wang gives the example of high speed rail lines in China (Beijing-Shanghai) and California which both started in 2008. The line in China actually got built in 3 years and completed 1.3bn trips in its first 10 years. The Californian one may never get completed and has already experienced high cost overruns. Engineering states can give rise to manufacturing ecosystems like Shenzhen. There is an element of raw state capacity to do things on display in engineering states where building things can often override niceties like property rights in order to make progress.

Engineering states can also go catastrophically wrong, with examples including the one-child policy and zero-covid. An economic example is the recent tech crackdown which slowed dynamism in China’s private sector or the side-effects of its intervention in property markets and the sky-high individual savings rates. Engineering societies often try to go as far as to control thought or discourse.

By contrast, societies that get bogged down in red tape (lawyerly ones) often don’t succeed at building anything leading to the expectation of stagnation. This is particularly dangerous as citizens in stagnant societies will not expect progress nor agitate for policies that lead to progress. There is the benefit of strong property rights and a much higher willingness to take risks and invest in societies with a strong rule of law.

Another downside of a lawyerly society is that if society is run by lawyers (as many top politicians are) there is a tendency to reach for rules and regulations as the solution to everything. There’s often a missing appreciation of how much cost this imposes on making progress.

While Wang does praise engineering state capacity, he noted after living both types of societies: "After six years in China, I missed pluralism. It is wonderful to be in a society made up of many voices, not only an official register meant to speak over all the rest. I missed the ambient friendliness of Americans combined with a government that mostly leaves people alone. Most of all, I missed the ability to order books."

Lessons for Us

All three of these books grapple with different elements of “What does it take to keep this golden age going?”

Some of the lessons I drew from reading these books and thinking about their implications:

- Openness to trade, ideas, and people has been a marker of a strong civilization. When these close down it would be a bad sign. It’s possible that the internet has fundamentally limited how closed down society can be and “it’s different this time.” However, there are some signs that it’s possible to control digital communication too and so we should still be vigilant that we remain open.

- Different institutions and organizational structures have different strengths and they must adapt over time. They’re not all equally adapted to all challenges, so we’ll need to find a way to improve our ability to respond to challenges without compromising the core principles of a successful civilization.

- Golden ages can end due to external threats. The Abbasid Caliphate reached for an alliance with religion to fend off external threats (first Crusaders, then the Mongols). The Dutch Republic, after the disaster year of 1672 (the Rampjaar) led to closing down the previously open society and converted the meritocracy to an aristocracy.

- Success can plant the seeds of decline. As a society becomes successful, members at the top of society will try to freeze society so that they can maintain their power. This can take the form of state capture or orthodoxies that must not be violated. There’s a tendency to lead to over-centralization or stagnation to entrench existing winners.

- Progress leads towards technological revolution. The invention and refinement of the cannon meant that castles became obsolete. As castles were no longer effective, fragmented small kingdoms which were the cradle of the renaissance gave way to larger, centralized European states.

- AI represents fundamental change. How do our institutions best adapt to this changing world? Stagnation is not the answer but every solution carries some risk. How do we best face this as a society?

These three books illuminate where we stand and where we’re headed. And golden ages are not something to take for granted.

Here are some quotes that stood out to me from the 3 books.

Peak Human:

Tom Holland suggests that it was Themistocles himself, the great spin-doctor, who created the myth about the noble sacrifice at Thermopylae, in order to stiffen the spine of reluctant Spartans and other Greeks... If this theory is correct, Sparta's proudest moment was invented by a trickster Athenian.

Europe suddenly found itself at the confluence of new ideas from abroad, expanding cities, a wealthier middle class, elements of law and a system of finance. It benefited from all of these – as well as an invaluable absence. I once had the pleasure of hearing the great libertarian theorist Tom G. Palmer summarizing world history in one sentence during a lecture. Out of his virtuoso knowledge of human societies and institutions, he chose, only half-jokingly: ‘The lesson from history is: don’t get invaded by Mongols.’

My daughter recently told me: 'Every time I study history, my reaction is, wow, I wouldn't want to live there.' She's right, of course. Prosperity, peace and progress are rare in human history. It has only been a normal state of affairs in some regions, in some eras, and every time it was eventually snuffed out. Don't take it for granted.

How Progress Ends:

Stated simply, centralized bureaucratic management is most advantageous for exploiting low-hanging technological fruit and spearheading technological catch-up, while decentralized systems are better for exploring new technological trajectories, which is the only way to make progress once the technological frontier is reached.

The most radical revolutionary will become a conservative on the day after the revolution.

As Alfred North Whitehead famously observed, "The great invention of the nineteenth century was the invention of the method of invention."

Breakneck:

Drive around America and China, on the other hand, and you'll see people and places that are utterly deranged. That's not a reproach. These two countries are messy in part because they are both engines for global change. Europeans have a sense of optimism only about the past, stuck in their mausoleum economy because they are too sniffy to embrace American or Chinese practices.

The trouble with Xi Jinping is that he is perhaps 60 percent correct on everything. He's driving toward a usually admirable long-term goal. But in the name of achieving change, the engineering state delivers such beatings on people or industries that they are unable to pick themselves back up again.

If you want to appreciate what Detroit felt like at its peak, it's probably better to experience that in Shenzhen than anywhere in the United States.